S. C. Suman: Continuity and Change in Mithila Painting

Just as it was a firingi none other than Sir George Abraham Grierson who first used the label ‘Maithili’ for the cross–border language of that name spoken in Nepal and India, so it was a firingi named William Archer who discovered Mithila painting and immortalized it in his 1942 article titled ‘Maithil Painting’ in Marg: A Magazine of the Arts wherein he published a number of photographs of Mithila wall paintings taken in 1940. Sadly, none of the wall paintings that Archer photographed exist today – the sole exception being a black and white photograph of a 1919 wall painting commissioned by Maharajadhiraja Rameshwar Singh of Darbhanga to decorate the kobarghar ‘nuptial chamber’ of the Rajnagar Palace for the marriage of his only daughter at the age of 9. The 1919 wall painting, photographed much later, happens to be the single oldest extant sample of Mithila painting, to date.

Soon after the introduction and availability of white paper and paint for painting during the late 1960s, the Mithila paintings tended to receive universal acclaim and Maithil women’s paintings fetched enviably higher and yet higher prices.

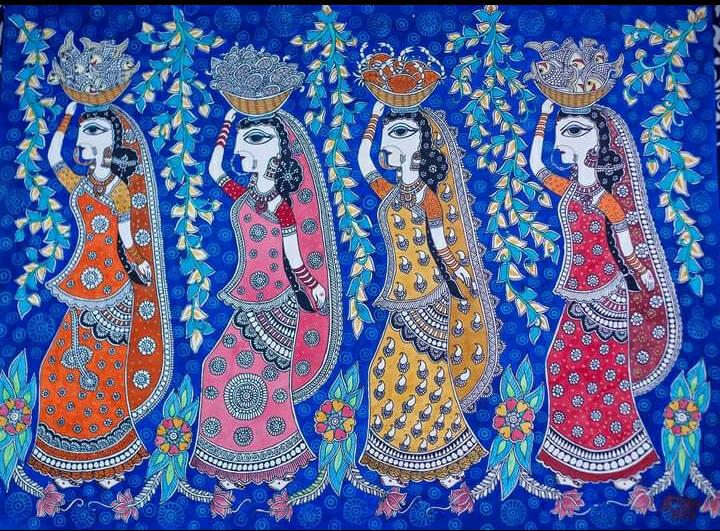

A cursory perusal of the literature of art–writing on Mithila paintings reveals a total of three broad strands: a) paintings done by mahapatr brahman women, b) paintings done by kayasth women, and c) paintings done by dusadh women. Sita Devi, a mahapatr brahman, epitomized the brahman women’s style of wall paintings that is now dubbed the bharni ‘filled’ style: her paintings were “generally of large, elegant, often elongated figures in bright colours, using a straw or bamboo stick, either frayed at the end, or with a rag or wad of cotton at the tip, to serve as a reservoir for the paint” (David L. Szanton, 2007). Ganga Devi, who is immortalized by Jyotindra Jain’s 1997 book titled Ganga Devi: Tradition and Expression in Mithila Painting, on the other hand, shot to fame with her “extremely detailed kachani or “line” paintings using fine nib pens and only black and red ink” (David L. Szanton, 2007). In sharp contradistinction as it were to the brahman and kayasth women, the dusadh women drew heavily upon auspicious godana ‘tatoo’ images that their arms and legs were densely filled with; instead of painting the traditional Hindu gods and goddesses, they focused on painting their own deities such as Raja Salhes and his coterie. Dusadh women painters such as Chano Devi, Lalita Devi are eminently famous today, and currently the “tattoo” paintings pass as distinctively and uniquely dusadh painting. Presently, gobar paintings and geru paintings have been appended as two additional newer facets to the dusadh painting. In spite of the marked stylistic variations, the paintings done by brahman, kayasth, and dusadh women continue to remain quintessentially Mithila painting.

My knowledge of Mithila painting is minimal: I have consented to pen these words at a very short notice upon a fervent, nay, persistent request from S. C. Suman. I was also emboldened in this act by virtue of having visited an exhibition of his paintings “Mithila Cosmos: Circumambulating the Tree of Life” held during December 10, 2013 – January 6, 2014. Needless to say, I was awe–struck and very favorably impressed with his paintings.

S. C. Suman is one of the few but famous male painters of Mithila painting. We have come to learn that he was a precocious child painter and that he was initiated into the trade by his grandmother – a constant source of encouragement and inspiration. No wonder, he bagged a number of awards in school and college competitions.

S. C. Suman, himself a kayasth by birth, tends to inherit all the traits of the kachani style, but he does not stop there. Not only did he excel in the “line” painting with an insatiable appetite and a penchant for very minute and miniscule details of line, but he also succeeded in creating an exemplary amalgamation of and a synthesis between the bharni and kachani styles of Mithila painting. On top of it, he has a singular distinction of adding a new dimension to Mithila painting by espousing textile design thereby incorporating amazingly intricate textural details of lines – surpassed perhaps only by the Thanka painting.

S. C. Suman has got a real knack for using natural pigment in his paintings: singarhar flowers for orange, gena flowers for tamarind yellow, poro seeds for purple/deep red dye, gobar ‘cow dung’ for greenish texture, bougainvillea flowers of many hues for crimson red and/or magenta reddish purple color – to name only the famous few. Suman’s discrete use of vegetable dye, no doubt, lends credence, authenticity, and naturalness to the paintings.

<br.

S. C. Suman also distinguishes himself with a flair for incorporating issues of contemporaneous political conflict and social disharmony prevalent in Nepal after the April 25, 2015 earthquake in his recent paintings. This affords an extended range, an elaboration, and an international appeal as it were to the contemporary paintings of S. C. Suman.

I may wish to close my remarks by describing S. C. Suman as a rather seasoned and iconic painter of Mithila paintings.

Ranju Yadav: Tradition and Individual Talent in Mithila Painting

The genre of ‘Mithila Painting’, surreptitiously labeled and famed across the globe as the umbrella term ‘Madhubani Painting’, is notoriously beleaguered with stridently stark sexism: barring an infinitesimally small number of ‘male’ artists, most painters worth their salt persist to be ‘females’ of all hues and from all communities, and a considerable corpus of this ritual art is indeed painted by women.

Mithila Painting is by now susceptible to unique commoditization; it is also shrouded in a subdued controversy in that the young apprentice women painters are systematically subject to financial exploitation. It’s no wonder therefore that most, if not all, visitors to the Janakpur Nari Vikasa Kendra situated in a small village near the town of Janakpur happen to be the firinghees.

The odyssey of the Mithila Painting from a modest rural village to the sophisticated Amazon.com in New York (fetching inordinately exorbitant prices in US dollars) has drastically altered its local character into global, as a subterfuge as it were. The arrival of Western art–scholars into the rural arenas of India and Nepal and the subsequent international travel of the local Indian and Nepalese women artists to countries such as Japan, Germany, France, and the United States of America have also tended to reconfigure the quintessential ritualistic, ceremonial and/or decorative moorings of the Mithila Painting into crude commercialization and, one might add, deterritorialization.

The standard discourse of the poetics of the Mithila Painting is characterized by “line drawings filled in by bright colors and contrasts or patterns” (Jyotindra Jain 1997) as well as a complex cluster of a plethora of tribal and/or archetypal motifs i.e. fish, parrot, elephant, turtle, snake, sun, moon, bamboo tree, lotus, etc. Ever since William G. Archer – an Honorable East India Company Servant – published his famous 1949 paper titled the “Maithil Painting” in Marg (Bombay), a host of scholars from across the globe have followed suit – all assiduously endeavoring to critique and explicate the “meanings” inherent in the rather innocent–looking but intricately structured art–works of the Mithila Painting. One such study stands out prominently and deserves special mention: Carolyn Henning Brown’s (1996) paper published in the American Anthropological Association journal American Ethnologist has ably succeeded in both contesting and deconstructing the preponderant colonial academic interpretation of the overbearing nuances of tantra and eroticism in the repertoire of the Mithila Painting trope.

Ranju Yadav – coming as she does from a “differently positioned” community – stands apart as a distinctly superior painter owing to her masterly handling of the contemporary societal issues and the unique craft of the Mithila Painting. In sharp contradistinction to women painters of the brahman and kayasth communities, Ranju Yadav discretely selects themes for her paintings from around her familiar locale. Displaying a rather Feminist bias, she harps on such themes as the women’s emancipation (embodied in a caged woman being set free by a woman), the women’s empowerment (enshrined in a woman engaged in a fierce fight with a vicious bull), the age–old custom of dowry (showcasing in a baradhatta ‘cattle market’ depicting rather made–up bridegrooms as oxen on sale) – to list only the famous few. A number of her paintings also elaborate on the themes of State’s acute apathy to the flood–stricken victims, child marriage, girl child–embryo killing, caste–based discrimination, dowry–related bridal burning, and so on. Not all of her paintings are permeated with the overt motive of social reforms though: aesthetically highly pleasing and cheerfully decorative chauk paintings (done on ground in the courtyard with rice flour paste on the festive occasion of bhardutiya, Skt. bhratridvitiya) and the purain pat ‘water–lily leaf–like’ mokh paintings done on both sides of the front door of the main house appear to be RanjuYadav’s special preserve.

In an earlier Catalogue–Essay written in 2016 for a by–now famous ‘male’ painter, S. C. Suman, I had listed a total of three broad strands of the Mithila Painting, to date: (i) paintings done by the mahapatr brahman women, (ii) paintings done by the kayasth women, and (iii) paintings done by the dusadh women. Prima facie, that pervasive picture may appear to continue to hold until today; nonetheless, with the emergence of a young but brilliantly consummate artist, RanjuYadav, – endowed as she is with a remarkable individual talent – a new vibrant dimension might, just might, actually be suitably added to the abovementioned list as the fourth strand consisting of admirable paintings done by the yadav women.

I wish RanjuYadav luck on her first solo exhibition to be held in the Kathmandu Nepal Art Council Gallery during 30 March through 3 April 2019.